The stifle joint of the horse is designed similarly to the human knee, in that it is the joint between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia, with a “knee cap,” the patella, that resides in the front of the joint. The stifle joint can be identified at the front of the hind leg, just around and below the conjunction of skin to the abdomen on a healthy-weight horse. The bony lump that can be felt at the top of the joint is the patella, and the dip immediately below is the stifle joint. The stifle joint is the largest joint in the horse’s body.

The stifle joint of the horse is designed similarly to the human knee, in that it is the joint between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia, with a “knee cap,” the patella, that resides in the front of the joint. The stifle joint can be identified at the front of the hind leg, just around and below the conjunction of skin to the abdomen on a healthy-weight horse. The bony lump that can be felt at the top of the joint is the patella, and the dip immediately below is the stifle joint. The stifle joint is the largest joint in the horse’s body.

Conformation and Anatomy

The stifle should be level in height to the elbow of the horse, and for a stronger hind leg, the joint should be placed forward so that the thigh is more rectangular in shape, as opposed to a V shape when placed further back. Also, when placed further back it indicates that the horse has a shorter femur and, generally, will not have as much power. Full muscling over the joint, indicating better strength, contributes to the rectangular shape from both the side and rear views. When looking from the rear, the stifle should be the widest part of the hind quarters.

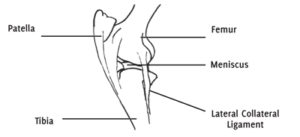

At the bottom of the femur are two rounded bone structures called condyles, one medial (towards the centre of the horse) and one lateral (towards the outside of the horse). Stabilizing the joint at the top of the tibia is the tibial spine, a narrow ridge, which fits neatly between the condyles. Between the junction of the tibia and femur are C shaped cartilages called menisci (singular = meniscus) which keep the joint in position and absorb shock.

The patella rides in the trochlear groove, a crease between the condyles on the femur, which helps to reduce friction and catalyzes extension power from the femur to the tibia.

The term “stifle joint,” however, actually refers to two separate joints that make up the collective stifle. The first is the femoro-tibial joint which, as the name suggests, connects the femur and tibia. The second is the femoro-patellar joint which connects the femur and patella. The femoro-patellar provides the largest articulation of the stifle. Both joints of the stifle have their own joint capsules whose linings produce synovial fluid which serves to lubricate the joint surfaces.

The stifle and hock joint share reciprocal action. Essentially, this means that the stifle and hock extend and flex in unison. The superficial digital flexor muscle and gastrocnemius muscle, which run down the back of the leg, are responsible for the reciprocal movement, and thus are collectively referred to as the reciprocal apparatus.

Function in Movement

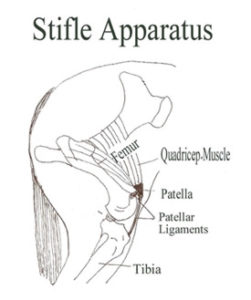

The extension of the stifle (when the leg straightens to push off) is achieved by a large fan-shaped muscle group (comprised of four parts) which originates on the lower pelvis and along the femur. All four muscles in this group insert on the patella. When these muscles contract, they pull the patella upwards acting on the patellar ligaments and, in turn, straighten the tibia in relation. Since the hock and stifle essentially act on the same purpose, the power is transferred downwards and the horse pushes off.

The flexion of the stifle (when the angles close towards the horse’s body) is created by a large number of muscles acting from a distance as well as some which directly activate the joint. One of these, the politeus muscle, which originates on the lateral (outside) condyle of the femur and inserts on the inside of the tibia primarily flexes the stifle but is also responsible for slightly rotating the leg inward.

The stifle requires strength to be powerful, but unfortunately, its design predisposes it to injury. The muscles that cover and activate the joint primarily run across the side of the joint, but not over it. This means that there is really only ligaments which cover the front of the joint. Over-exertion or any problems in those ligaments can drastically hinder the horse’s ability.

Problems in the Stifle

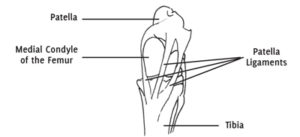

Probably one of the most common disorders of the stifle is upward fixation or displacement of the patella (also referred to as a locked stifle). Horses with straight hind limbs are most commonly affected, although horses with trauma to the patella or muscle deterioration are also affected. This disorder is when the patella, the kneecap, gets stuck within the condyles of the femur when the leg is in an extended position. The stifle and, coincidentally, the hock joint will get locked in a straightened position, though the fetlock is still movable.

The locked stifle can either be a permanent fixation (which requires veterinary attention) or, more difficult to assess, is the periodical upward fixation of the patella. In the periodical, the stifle joint will intermittently lock and release, much like the joint continuously “popping,” as the horse moves (most predominantly noticeable on a circle). This causes a great deal of pain and any manipulation of the stifle joint will likely cause a reaction.

Treatment for mild cases is trotting exercises and hacks to develop the muscle that supports the side of the joint. Avoidance of sharp turns is best to prevent further periodical fixation of the patella. Anti-inflammatory medication will help relieve the pain associated with the disorder. For severe cases where the joint is locked in extension, surgically cutting the medial patellar ligament will resolve it.

Overview

A healthy stifle is essential for maximum performance. Proper conditioning to ensure adequate muscling alongside the joint is paramount to prevent avoidable lameness and will help you achieve the most success with your horse.