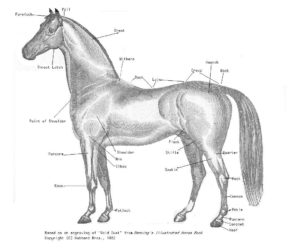

The croup on the horse is identified as the area along the topline from the loins to the base of the tale. From the side, the point of the croup should be in alignment with or just behind the point of the hip which is the bony protrusion at the front of the haunches which also marks the front of the pelvis. The croup should be fairly long from the point of the hip to the point of the buttock (which indicates the rear of the pelvis) to provide more leverage and power to the muscles in between. In height, the point of the croup, the highest point of the sacrum, should be level with or lower than the wither. Variations of this occur between breeds since some breeds, such as drafts and Shetlands, tend to be higher in the croup which can accommodate breed-specific work, but it is generally less desirable for most movement and longevity. Having “uphill” conformation (croup is lower than the withers), is generally considered better than the reverse because it shifts the horse’s centre of gravity forwards and enables the hindquarters to step more underneath the body. This type of conformation also tends to be easier to fit saddles to.

Different angles of the croup, which are measured from the point of the hip to the point of the buttock, warrant their own explanations, for the differences can have drastic effects on the movement and athletic strengths of the horse. Two variations of croup conformation include flat and steep croups which are discussed below.

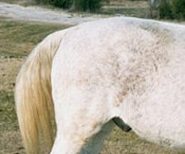

A flat croup is one whose angle is nearer to parallel to the ground. This conformation is usually also associated with having a longer croup. With both aforesaid characteristics, the horse tends to have a longer, ground-covering stride. Dressage horses are often preferred to have low, flat croups to allow more movement and so the horses are bred to have them. Endurance riders take pleasure in the benefits of the Arabian who tend to have flat croups which enables more ground-coverage. But don’t be fooled. Horses with high-set tails can be deceptive visually, appearing to have flatter croups than they actually do. Also, sway-backed horses can develop flatter croups over time as their anatomy starts to sag a little with age.

A flat croup is one whose angle is nearer to parallel to the ground. This conformation is usually also associated with having a longer croup. With both aforesaid characteristics, the horse tends to have a longer, ground-covering stride. Dressage horses are often preferred to have low, flat croups to allow more movement and so the horses are bred to have them. Endurance riders take pleasure in the benefits of the Arabian who tend to have flat croups which enables more ground-coverage. But don’t be fooled. Horses with high-set tails can be deceptive visually, appearing to have flatter croups than they actually do. Also, sway-backed horses can develop flatter croups over time as their anatomy starts to sag a little with age.

A steep croup is one whose angle is inclined more vertically than horizontally, and is often called “goose-rumped.” This conformation type reduces the range of motion of the hindquarters and also tends to have shorter distance along the croup, which provides less room for sufficient muscle attachment. In severe cases, the angle itself reduces the speed and efficiency for the horse’s travel, however it can also improve the hind-end’s ability to be under itself which is particularly helpful for activities such as barrels, reining or cutting. Some breeds have this type of croup for advantages to their breed-specific events or movement. The Walking Horse, for example, tends to have a steep croup for their unique gaits, and Drafts with this conformation can gain leverage for heavy pulling.

A steep croup is one whose angle is inclined more vertically than horizontally, and is often called “goose-rumped.” This conformation type reduces the range of motion of the hindquarters and also tends to have shorter distance along the croup, which provides less room for sufficient muscle attachment. In severe cases, the angle itself reduces the speed and efficiency for the horse’s travel, however it can also improve the hind-end’s ability to be under itself which is particularly helpful for activities such as barrels, reining or cutting. Some breeds have this type of croup for advantages to their breed-specific events or movement. The Walking Horse, for example, tends to have a steep croup for their unique gaits, and Drafts with this conformation can gain leverage for heavy pulling.

To the enthusiastic horse-owner, it is beneficial to be aware of all the pros and cons of conformation so that you can choose a horse that is not only mentally appropriate for you as a mount, but anatomically prepared for the type of riding you wish to pursue. To understand the reasons why your horse may have difficulty with some areas of training but excel at others will help you plan your training goals, and with understanding, your relationship with your horse will undoubtedly improve.